Moonshining: An Ozarks Side Gig

April 14, 2021

Sheila Harris

It’s been 100 years since the United States lived under the restrictions of “Prohibition,” a period of 13 years when the manufacture, transport and sales of alcoholic beverages were federally illegal.

The Prohibition led to black-market sales and a rise in violent crime as federal agents and local law enforcement officials attempted to enforce the laws.

While mobsters and crime bosses controlled the black market in urban areas, the production of moonshine proliferated in the Ozarks and continued long after Prohibition ended. The last record of an illegal still confiscation in the Ozarks was in McDonald County in 1976, according to a 1991 Joplin Globe article by Andy Ostmeyer.

With Ostmeyer’s permission, much of the following information is drawn from the same article. Photos and additional information were provided by The Barry County Museum, as well as from the memories of local residents.

“The making of moonshine may well be the stepchild of Ozarks crafts,” said The Globe article.

In 1976, authorities found a Powell man making moonshine “hillbilly style,” after the man started buying hundreds of pounds of sugar at a time.

“You don’t buy that much sugar just to can huckleberries,” said Barry County sheriff (at the time), Vernon Still. It was the last recorded bust in Barry and McDonald Counties.

Sugar, malt, yeast, and corn were the common ingredients for the mash distilled into illegal whiskey in the Ozarks. Although the how-to of making moonshine had been passed down through the generations – primarily from the Scots -Irish immigrants who had settled the area – its production reached a zenith when the federal government passed the National Prohibition Act (or Volstead Act) which went into effect on January 17, 1920, and continued until 1933. Illegal moonshine production in Barry County, however, didn’t cease with the end of Prohibition, in part because the sale of illegal moonshine was a source of income for many residents during the Depression which followed Prohibition.

Corn was in plentiful supply in Barry County, as were the hills and hollows needed to provide cover for illicit activities.

Dry Hollow, between Washburn Prairie and Roaring River, was the stomping grounds of “Dry Hollow Slim,” a notorious moonshiner who made the valley echo with the muffled sound of thunder from the thump keg on his distillery between 1951 and 1952. His son, a former Monett businessman who prefers to remain unnamed, said he learned the craft from his father, but did not pass the knowledge on to his own children.

“Lifestyles change,” he said, “and some skeletons are better off buried.”

Dry Hollow Slim died in 1979, nine years prior to 1988, the first year since Prohibition when no illegal stills were raided by federal agents. Prior to that, in 1932 – the last year of Prohibition – the seizures of stills in the nation reached a peak of 23,165, according to Les Stanford, spokesman for the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms. By 1950, federal seizures fell to 10,000 nationwide, and by 1970, to 5,000. Ten years later it hit 106, and in 1985, eight. In 1988, it hit zero.

In spite of the fact that, today, raids on illegal moonshine stills in Barry County are virtually unheard of, many residents carry memories of stories passed down from older family members.

Jill Holman LeCompte has such memories.

Her father (Calvin Holman) told her, when she was in grade school, that if kids didn’t like her, not to worry about it; it might not have anything to do with her.

“It might be because your grandfather shot up their grandfathers’ moonshine stills,” Holman told her.

Jill LeCompte’s grandfather, Bill Holman, was a sheriff of Barry County from 1928 – 1932 during the final years of Prohibition.

His office saw plenty of activity relating to illegal moonshining, as did those of his predecessors. Court dockets and newspapers printed in Barry and Lawrence Counties during Prohibition were filled with accusations of “Possession of Intoxicating Liquor,” and courtrooms overflowed with eager spectators at the trials of those who were brought before a judge.

When searching for the illegal manufacture of moonshine, the suspicions of law enforcement were easily aroused. According to old newspaper clippings, it wasn’t just stills that caught their eyes. Residents in possession of empty raisin boxes (another possible mash ingredient) and large quantities of sugar caught their attention as well.

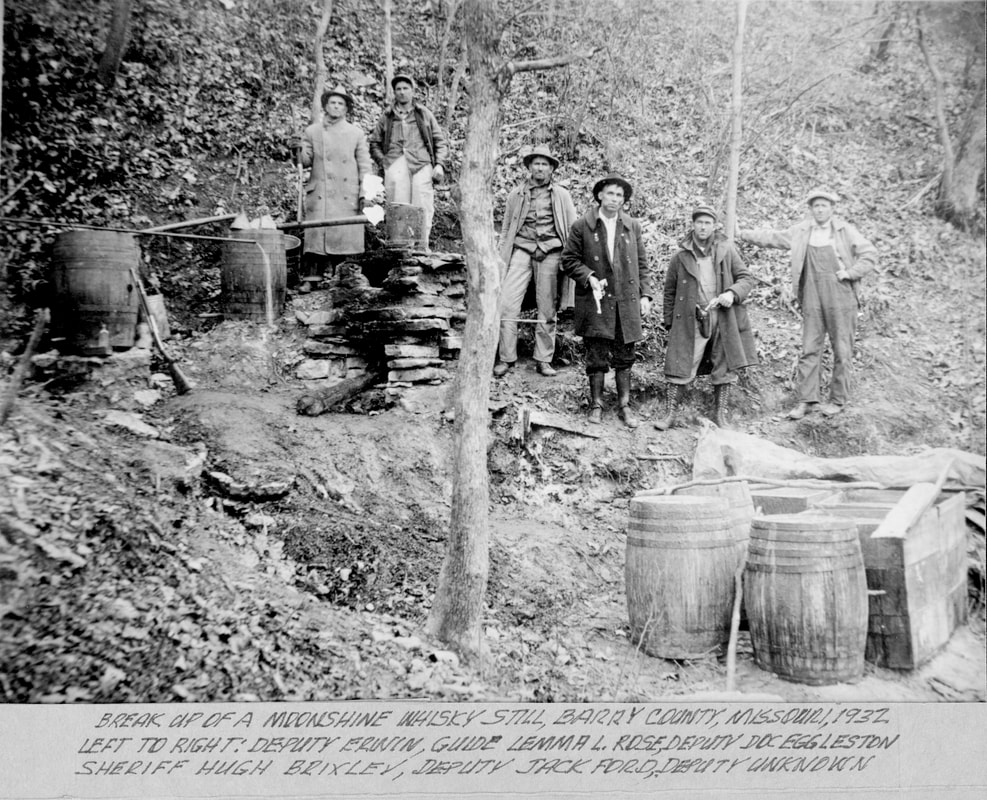

Hugh Brixey, Barry County sheriff from 1924 – 1928, whose office had been holding confiscated moonshine accumulated over a period of several months - held a huge outpouring of alcoholic beverages outside the county jail on an occasion noted in a news clipping. About 150 gallons of moonshine, wine and other intoxicants were poured into the gutter; the odor from it could be detected a block or two away, it was reported.

While Jill LeCompte’s grandfather was out shooting up moonshine stills, Ed Fink’s grandfather was tasked with trying to hide his family’s still.

“I was raised down on Flat Creek, in Piney Holler,” Fink said. “It was a pretty isolated area, so isolated that when I was out of school for the summer, I didn’t see anyone except people who floated down Flat Creek occasionally.

“I grew up hearing stories from my grandfather about his family’s moonshining. During the Depression it was a way for some people around here to make a little extra money, I guess. Times were really hard, they said. Granddad told me when he was just a young teenager, he had to go out and move his family’s still from one location to another so some hunter didn’t accidentally stumble onto it,” Fink said. “If they found it, they’d feel obligated to report it to the sheriff, granddad said. He said they were more worried about neighboring hunters finding it, than they were about federal law enforcement agents.”

According to the referenced Joplin Globe article, it was common for moonshiners to rat each other out to law enforcement, as a way of diverting attention from their own illegal activities.

Since the restrictive legislation of Prohibition was lifted in 1933, the manufacture of distilled whiskey - except for household use - is illegal without federal and state permits.

The sale of distilled whiskey is entirely prohibited without such permits. Even with the proper permits, the list of regulations which accompanies the permits is prohibitively long.

With Prohibition lifted, tax revenue from legal liquor sales is funneled into public coffers, as are tax revenues from other sources considered by many to be vices.

Whether that’s considered a good thing depends entirely on a person’s perspective.

Sheila Harris

It’s been 100 years since the United States lived under the restrictions of “Prohibition,” a period of 13 years when the manufacture, transport and sales of alcoholic beverages were federally illegal.

The Prohibition led to black-market sales and a rise in violent crime as federal agents and local law enforcement officials attempted to enforce the laws.

While mobsters and crime bosses controlled the black market in urban areas, the production of moonshine proliferated in the Ozarks and continued long after Prohibition ended. The last record of an illegal still confiscation in the Ozarks was in McDonald County in 1976, according to a 1991 Joplin Globe article by Andy Ostmeyer.

With Ostmeyer’s permission, much of the following information is drawn from the same article. Photos and additional information were provided by The Barry County Museum, as well as from the memories of local residents.

“The making of moonshine may well be the stepchild of Ozarks crafts,” said The Globe article.

In 1976, authorities found a Powell man making moonshine “hillbilly style,” after the man started buying hundreds of pounds of sugar at a time.

“You don’t buy that much sugar just to can huckleberries,” said Barry County sheriff (at the time), Vernon Still. It was the last recorded bust in Barry and McDonald Counties.

Sugar, malt, yeast, and corn were the common ingredients for the mash distilled into illegal whiskey in the Ozarks. Although the how-to of making moonshine had been passed down through the generations – primarily from the Scots -Irish immigrants who had settled the area – its production reached a zenith when the federal government passed the National Prohibition Act (or Volstead Act) which went into effect on January 17, 1920, and continued until 1933. Illegal moonshine production in Barry County, however, didn’t cease with the end of Prohibition, in part because the sale of illegal moonshine was a source of income for many residents during the Depression which followed Prohibition.

Corn was in plentiful supply in Barry County, as were the hills and hollows needed to provide cover for illicit activities.

Dry Hollow, between Washburn Prairie and Roaring River, was the stomping grounds of “Dry Hollow Slim,” a notorious moonshiner who made the valley echo with the muffled sound of thunder from the thump keg on his distillery between 1951 and 1952. His son, a former Monett businessman who prefers to remain unnamed, said he learned the craft from his father, but did not pass the knowledge on to his own children.

“Lifestyles change,” he said, “and some skeletons are better off buried.”

Dry Hollow Slim died in 1979, nine years prior to 1988, the first year since Prohibition when no illegal stills were raided by federal agents. Prior to that, in 1932 – the last year of Prohibition – the seizures of stills in the nation reached a peak of 23,165, according to Les Stanford, spokesman for the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms. By 1950, federal seizures fell to 10,000 nationwide, and by 1970, to 5,000. Ten years later it hit 106, and in 1985, eight. In 1988, it hit zero.

In spite of the fact that, today, raids on illegal moonshine stills in Barry County are virtually unheard of, many residents carry memories of stories passed down from older family members.

Jill Holman LeCompte has such memories.

Her father (Calvin Holman) told her, when she was in grade school, that if kids didn’t like her, not to worry about it; it might not have anything to do with her.

“It might be because your grandfather shot up their grandfathers’ moonshine stills,” Holman told her.

Jill LeCompte’s grandfather, Bill Holman, was a sheriff of Barry County from 1928 – 1932 during the final years of Prohibition.

His office saw plenty of activity relating to illegal moonshining, as did those of his predecessors. Court dockets and newspapers printed in Barry and Lawrence Counties during Prohibition were filled with accusations of “Possession of Intoxicating Liquor,” and courtrooms overflowed with eager spectators at the trials of those who were brought before a judge.

When searching for the illegal manufacture of moonshine, the suspicions of law enforcement were easily aroused. According to old newspaper clippings, it wasn’t just stills that caught their eyes. Residents in possession of empty raisin boxes (another possible mash ingredient) and large quantities of sugar caught their attention as well.

Hugh Brixey, Barry County sheriff from 1924 – 1928, whose office had been holding confiscated moonshine accumulated over a period of several months - held a huge outpouring of alcoholic beverages outside the county jail on an occasion noted in a news clipping. About 150 gallons of moonshine, wine and other intoxicants were poured into the gutter; the odor from it could be detected a block or two away, it was reported.

While Jill LeCompte’s grandfather was out shooting up moonshine stills, Ed Fink’s grandfather was tasked with trying to hide his family’s still.

“I was raised down on Flat Creek, in Piney Holler,” Fink said. “It was a pretty isolated area, so isolated that when I was out of school for the summer, I didn’t see anyone except people who floated down Flat Creek occasionally.

“I grew up hearing stories from my grandfather about his family’s moonshining. During the Depression it was a way for some people around here to make a little extra money, I guess. Times were really hard, they said. Granddad told me when he was just a young teenager, he had to go out and move his family’s still from one location to another so some hunter didn’t accidentally stumble onto it,” Fink said. “If they found it, they’d feel obligated to report it to the sheriff, granddad said. He said they were more worried about neighboring hunters finding it, than they were about federal law enforcement agents.”

According to the referenced Joplin Globe article, it was common for moonshiners to rat each other out to law enforcement, as a way of diverting attention from their own illegal activities.

Since the restrictive legislation of Prohibition was lifted in 1933, the manufacture of distilled whiskey - except for household use - is illegal without federal and state permits.

The sale of distilled whiskey is entirely prohibited without such permits. Even with the proper permits, the list of regulations which accompanies the permits is prohibitively long.

With Prohibition lifted, tax revenue from legal liquor sales is funneled into public coffers, as are tax revenues from other sources considered by many to be vices.

Whether that’s considered a good thing depends entirely on a person’s perspective.